The Oxford comma is subject to debate. It is the comma before the word “and” in a series. For example, “bread, eggs, and milk.” The comma between “eggs”and “and” is called the Oxford or serial comma. It separates all of the parts of a list.

The Oxford comma is subject to debate. It is the comma before the word “and” in a series. For example, “bread, eggs, and milk.” The comma between “eggs”and “and” is called the Oxford or serial comma. It separates all of the parts of a list.

Some style guides tell you to use it and some tell you not to. The Gregg Reference Manual calls for the Oxford comma (¶ 162a).

The thing I always remember that encouraged me to use the Oxford comma was an example of a will that left property to John, Joe and Sarah. If you are literal (as most lawyers are), you could say that the property was left half to John and half to Joe and Sarah to share. If you add the Oxford comma between “Joe” and “and,” there is no question that the property is to be divided into three parts—one for John, one for Joe, and one for Sarah.

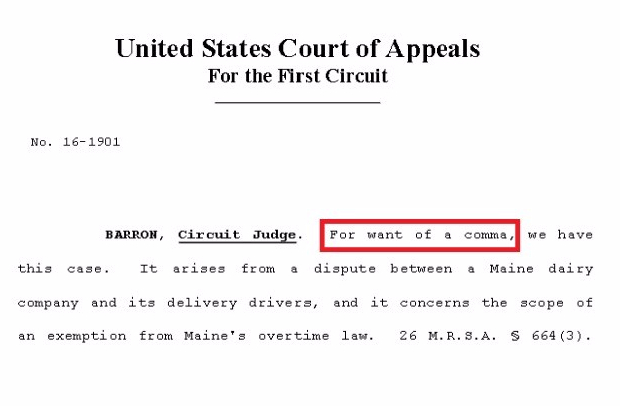

In my opinion, it is one small piece of punctuation that can make a huge difference in the meaning and intent of what you are writing. In fact, as most of you may have heard, just last week, an appellate court ruled in a Maine labor dispute based on the Oxford comma. The case was about dairy drivers who argued that they were entitled to overtime pay for certain tasks. The company said they were not entitled to that overtime. The appeals court ruled that the guidelines on activities entitled the drivers to overtime pay because the guidelines were too ambiguous due to the lack of an Oxford comma.

Here is the law’s wording about activities NOT meriting overtime pay:

The canning, processing, preserving, freezing, drying, marketing, storing, packing for shipment or distribution of:

(1) Agricultural produce;

(2) Meat and fish products; and

(3) Perishable foods.

Based on this language, is packing for shipment its own activity or is it packing for the distribution of the three things on the list? If an Oxford comma had separated “packing for shipment” and “or,” the meaning would have been much more clear. According to court documents, the drivers arguing for overtime actually distribute perishable food, but they do not pack it. That argument helped win the case.

The circuit judge said that had the language used the serial comma to mark off the last of the activities in the list, “then the exemption would clearly encompass an activity that the drivers perform.” Since the serial comma was not there to mark off the last of the activities, the judge obeyed the labor laws which, when ambiguous, are designed to benefit laborers and the case was settled.

“For want of a comma, we have this case,” the judge wrote.

But even worse than that is the fact that there are guidelines on how Maine lawmakers are to draw up their documents that do NOT include Oxford commas, so they followed the guidelines they were given. At least they followed the guidelines last week. This week, that guideline may have changed.

Follow

Follow