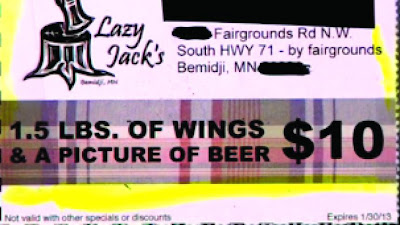

Seems kind of high priced for wings and a PICTURE of beer . . .

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Archives

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- August 2023

- June 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

Categories

- abbreviations

- apostrophes

- articles

- Ask PTB

- Autocorrect

- brand names

- capitalization

- commas

- confusing words

- conjunctions

- contractions

- dashes

- dates

- definitions

- double negatives

- ellipsis

- Emphasis added

- font

- footnotes

- foreign words

- grammar

- grammar giggles

- headings

- holidays

- homophones

- hyphenation

- In The News

- infinitives

- italics

- legal assistant

- legal proofreading

- legal secretary

- misspellings

- money

- nonessential phrases

- numbers

- paralegal

- period

- plural

- possessives

- postscript

- prepositions

- professional titles

- proofreading

- proofreading resources

- punctuation

- question marks

- reflexive pronouns

- search and replace

- semicolons

- singular

- slashes

- spacing

- Spell check

- style guides

- Time

- Uncategorized

- underlining

- Words of the Month

- Words of the Week

Follow

Follow